W1982 Hathor Emerging

{loadposition share}

W1982 Hathor Emerging from the Mountain

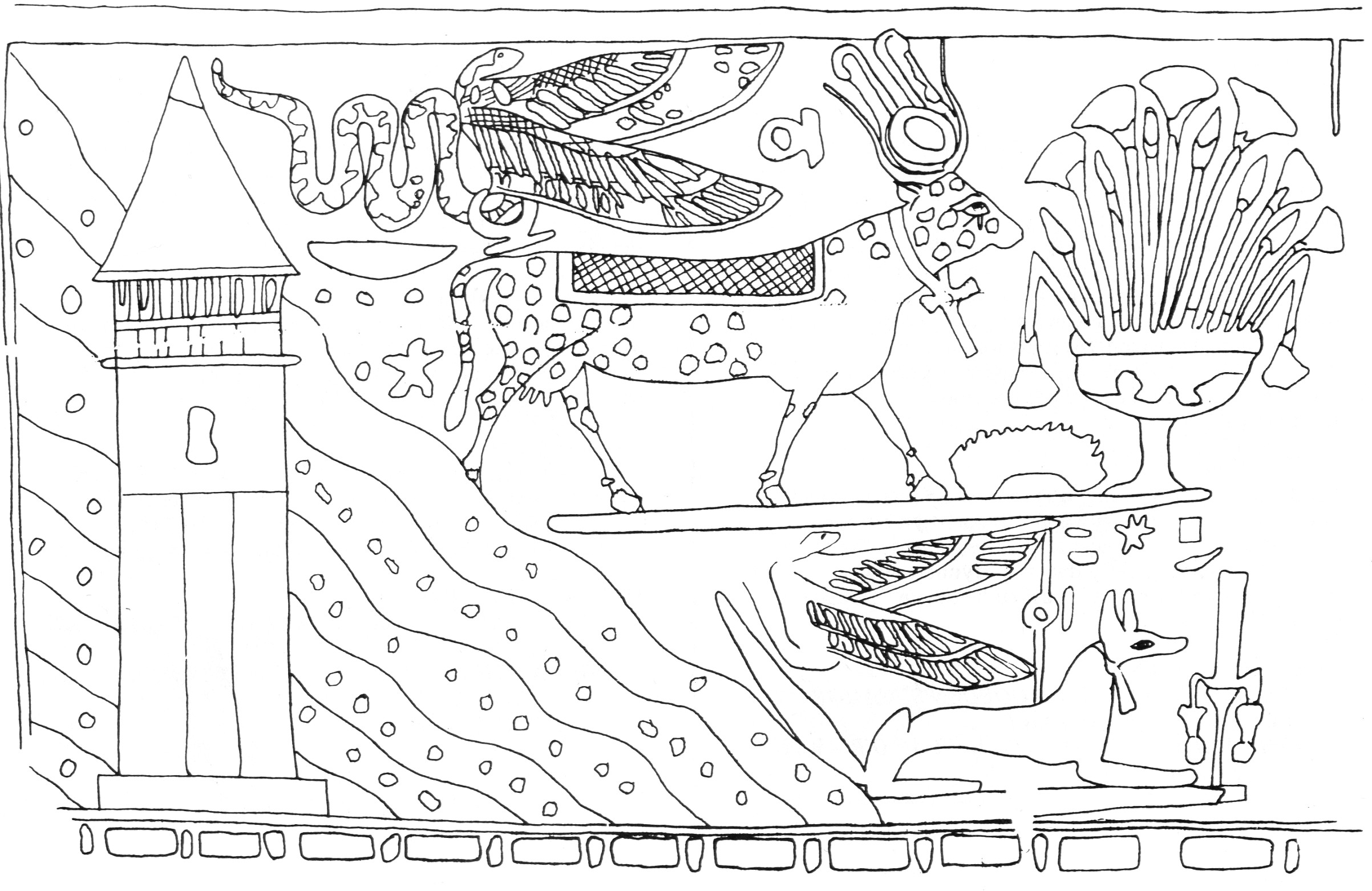

This is part of a scene from a coffin of a lady musician. The coffin is about 3000 years old. It shows the goddess Hathor in the shape of a cow emerging from the mountain in thebes to welcome the dead person to the afterlife.

The vignette shows a sacred speckled cow with saddle-cloth, Hathor, with an ankh around her neck and the atef crown on her head, coming out of the Western Mountain at Thebes. The mountain is speckled with stone nodules and in front of it stands a pyramidion-capped tomb. A winged serpent appears above the tomb and another is shown above Anubis who sits dog-like at the bottom. A clump of papyrus in a bowl is put in front of the cow deity. To the left the lady Chantress stands before an offering table making an offering toward the tomb.

The motif of Hathor coming out of the mountain is a common vignette of the 21st Dynasty Book of the Dead, Chapter 186 (Niwinski 1989, 140). The Chapter reads: Hathor, Lady of the West; She of the West; Lady of the Sacred land; Eye of Re which is on his forehead; kindly of countenance in the Bark of Millions of Years; a resting place for him who has done right within the boat of the blessed; who built the Great Bark of Osiris in order to cross the water of truth. On vignettes of this spell in the 19th Dynasty, a hippopotamus goddess is often present wearing the horns and sun disk of Hathor, along with the cow (Allen 1974, 209-219). Hathor may be shown as a hippopotamus.

As with the scene on the opposite side of this coffin (that of the sycamore tree goddess), Niwinski (2006) believes this scene may allude to an actual rite, perhaps offerings made to Hathor and Anubis at Hatshepsut’s temple at Deir el-Bahri. Certainly, the appearance of the papyrus in a bowl does not so much suggest an actual natural growing clump but is more indicative of a rite. The artificial vase is common in such scenes. For example, it appears on a similar coffin in Berman (1999:318, 328) and on the 22nd Dynasty coffin of Amenemope in the BM (Taylor 2001, pl. 169). The connection between this scene and that on the opposite side of the coffin is shown by the fact that in some depictions the two are combined (e.g. Bettum 2004, 94-95, fig. 26).

An inscription to the left of the tomb (at the foot of the coffin) seems to read:

Nwt wrt Htp aImntt Hwt-Hr

Nut the great, a funerary offering to Hathor.

The inscription on the tomb itself reads:

Dd mds in Hwt-Hr nbt Imnt

Recitation by Hathor, Lady of the West.

The type of tomb superstructure here depicted had ceased to be built by the Ramesside Period but continued to be depicted on coffins. It is a classic tomb structure of the village of Deir el-Medina with a pyramidion above the entrance. By the 21st Dynasty, because of the economic instability of Egypt, tomb robbing had put an end to elaborate decorated tombs and instead officials were buried in earlier tombs and with fewer grave goods. The attachment to depicting the old style tomb betrays a general conservatism which is usually associated with religious iconography not only in Egypt but elsewhere.

The figure appears on our coffin, as on the Oslo coffin (Bettum 2004, 95, fig. 26) with his kherep sceptre, and on the Oslo coffin is identified as Anubis. Anubis and Wepwawet appear to at times been interchangeable. DuQuesne (2005, 586) suggests a useful rough model for the differences ‘might be that Upwawet tends to have ‘masculine’ characteristics such as smiting enemies, while Anubis has a more ‘feminine’ role in tending the body for mummification and facilitating rebirth’. Anubis is a guide to the dead, a means by which there way to the afterlife is opened, and also a protector of the dead, a guardian of the necropolis. Wepwawet is also a guide, of the living and the dead. Wepwawet is often portrayed with a uraeus, a form of Wadjet. Indeed one inscription even states he was born in the sanctuary of the goddess Wadjet at Buto. The winged uraeus above the Hathor cow seems to be Neith (see above). Neith too could be portrayed as a winged serpent, the Eye of Re, and el-Sayed (1982 vol I, 71-72; vol 2 393-4) hypothesizes that she should be seen as the feminine doublet of Wepwawet. This is confirmed by DuQuesne (2005, 200, 201, 504, 514) who also adds that Neith also occasional has the title wp(t)-wAwt in tomb inscriptions and is associated with Anubis. The baton in front of him is a kherep sceptre with menits suspended from the handle.

General information on W1982

Other Book of the Dead items in the Egypt Centre

References:

Bettum, A. 2004. Death as an Internal Process. A case study of a 21st Dynasty coffin at the University Museum of Cultural Heritage in Oslo. Online publication accessed 25.6.2008, http://wo.uio.no/as/WebObjects/theses.woa/wa/these?WORKID=20317

DuQuesne, T. 2005.The Jackal Divinities of Egypt I. Oxford Communications in Egyptology VI. Oxford: Darengo Publications.

El Sayed, Ramadan, 1982. La déesse Neith de Sais. Le Caire : Institut Français d’Archéologie Oriental du Caire.

Niwinski, A. 2006. The Book of the Dead on the Coffins of the 21st Dynasty. In Backes, B., Munro, I and Stöhr, S. eds.Totenbuch-Forschugen. Gesammelte Beiträge des 2. Internationalen Totenbuch-Symposiums Bonn, 25. bis 29. September 2008. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 245-273.